Miranda Chance

Edited by Leah Gilbert

A couple of years ago, influencer Hannah Kae drew the attention of online critics for the unusual and slightly disturbing nature of her content. Through videos featuring awkward dances, improper eating habits, childish background music, and pigtail hairstyles, fans were given the impression that the adult influencer was trying to make herself seem like a child. Online users began to use the word “infantilization” to describe what Kae was doing.

Beth Birenbaum writes that young women may be infantilized, or treated like children, by a romantic partner as a means of gaining control. She adds that overindulgence in traditional gender roles can result in a parent-child-like dynamic in romantic relationships, leading to the romanticization of immature behavior and enabling the fetishization of childish characteristics. Thus, a popular influencer infantilizing herself obviously made many online users uncomfortable, and even slightly disturbed.

Jenny Fax is a Taiwanese designer based in Tokyo, and I imagine she hopes to invoke a similarly shocked reaction as Hannah Kae to her clothing designs. She seems to use her designs as a way of critiquing the infantilization of women by the fashion industry.

Wearing children’s clothing styles as an adult has been a theme in the fashion industry for decades. In the 90’s, the schoolgirl uniform gained popularity among young women for its functionality and simplicity. For decades, school girls have been finding creative ways to express themselves despite dress code restrictions, and the conventional uniform became a sort of canvas for self-expression. Be it a shortened hemline or a colorful bag, the schoolgirl uniform has stayed in style because of its ability to adapt to the wearer’s preferences. Similarly, the Japanese Lolita subculture developed to combat the presence of lolicon: the fetishization of prepubescent girls. The modest, old-style clothing of the Lolita subculture serves as a reminder that not everything done by women is for the attraction or pleasure of men.

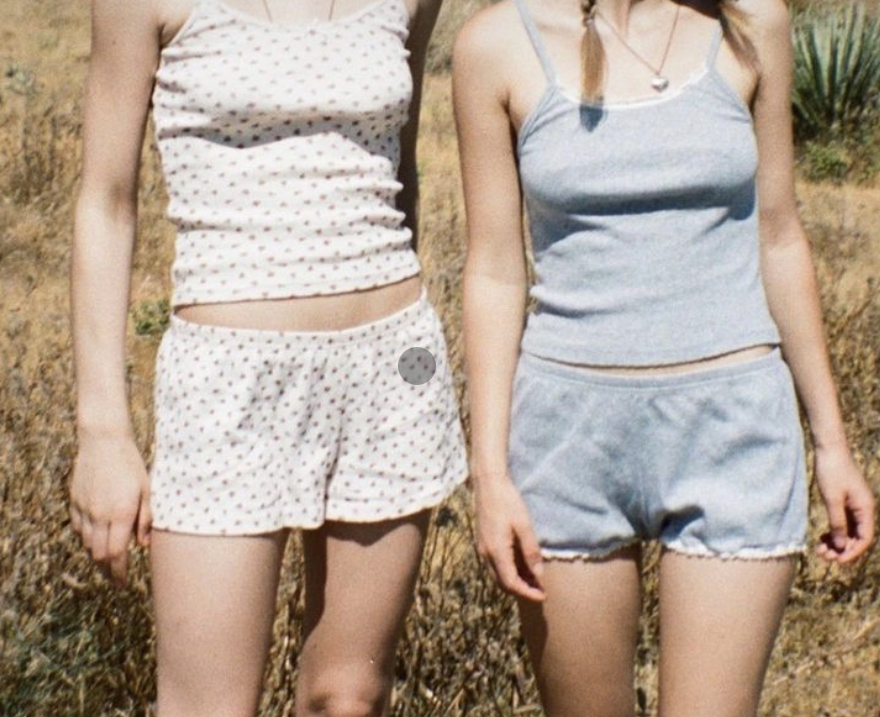

Obviously, there can be positive implications of especially youthful fashion styles, but as the trend cycle speeds up with the growing popularity of fast fashion, subcultures are less successfully gatekept from consumers who don’t understand the underlying implications of the clothes they wear. Thus, children’s clothing styles can easily be slipped into the trend cycle as a way of satisfying inappropriate fetishes without consumers noticing. A good example of this phenomenon is Brandy Melville’s “one size fits all” policy, which makes their clothes inaccessible to women with mature body types. The popularity of the brand gives consumers the impression that a less developed body is the beauty standard. The pastel and floral patterns that have become staples of the brand’s designs also further emphasize the appeal of a child-like disposition, resulting, in some cases, in the infantilization of the brand’s consumers.

However, in recent months I’ve noticed a trend of resisting this infantilization and subsequent fetishization. In contrast to Brandy Melville, Jenny Fax’s Autumn/Winter 2023 campaign takes youthful designs and presents them in an objectively unattractive environment. Blurry, poorly framed photos shot in a poorly lit Japanese garden give a slightly uncanny impression which I associate with horror movies. By fitting the models with somewhat disproportionate, plastic undergarments that are moulds of her own body, Fax succeeds in making the outfits look awkward and, thus, initially unappealing to consumers. As for the clothes themselves, frills, high necklines, and looser fits adorn the collection. These details – which are often associated more with childhood than ready-to-wear collections – and how they are presented remind the fashion industry of the original goal of girlish themes in clothing: serving the wearer, not necessarily the viewer.

Fax takes this idea further for Victoria’s Secret’s World Tour this last season. With the teenage girl as her muse, she took Victoria’s Secret’s classic lingerie and sewed it into awkward designs that don’t look at all comfortable to wear. When I first saw the collection, I was reminded of what it felt like to start wearing a bra as a preteen; when I first said goodbye to my younger self. Having been forced to recall my initial departure from my childhood dressing habits, I subsequently felt nostalgic for the little girl I used to be. I’ve noticed discussion online of nostalgia being the goal of more recent clothing trends. I think that this, similar to Lolita fashion, resists the fetishization of youthful aesthetics by brands like Brandy Melville. Recently, through details like ribbons, pastels, and ballet flats, women have been reclaiming the styles of our childhood. Our outfits are cute, but also sentimental and expressive of not only our present selves but also our past selves, which I think is so sweet.

Though Jenny Fax is not the pioneer of recent trends resisting the fetishization of the clothing styles of young girls, her newest collections are a good example of what these trends can look like. Through her implementation of sentimental styles, I am forced to think more critically about the use of these styles in my outfits. I look back on the little girl I once was, and how I can represent her in my clothing choices. She would’ve loved the flowy skirts and colorful handbags I’ve been sporting lately, and I think she might die if she saw my collection of sparkly costume jewelry. Thinking about my outfits this way makes them more special to me, and I feel an even stronger distaste for the fetishization of these trends. These days, I love to see the details of my peers’ outfits around campus that reflect that there is still some of our childhood left in all of us.